What Is Probable Cause and When Can Police Use It Against Me?

The issue of probable cause can come up when law enforcement officers decide to make an arrest, conduct a search of private property or when a person is prosecuted for a criminal offense. In the U.S. legal system, the concept of probable cause is based on language found in the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution.

Essentially, probable cause is used to ensure that people who are arrested and charged with crimes are arrested and charged for a valid reason. In this way, police officers are prevented from making arrests without reason and prosecutors are prevented from pursuing charges without evidence.

How Probable Cause Works

To understand the concept of probable cause, it is helpful to think of the rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. American citizens have the right to be free from unreasonable searches, seizures, arrests and prosecution. This means that, in order to arrest someone and charge them with a crime, a police officer must have a valid, reasonable belief that the person is guilty of the crime for which they are being arrested.

For example, imagine that a theft occurs and security camera footage shows a person in a blue shirt and dark pants fleeing from the scene. If the police encounter a person in a nearby neighborhood wearing those clothing items and carrying stolen merchandise, the police can reasonably decide that the person is responsible for the theft. They can then place that person under arrest for the crime.

This is because probable cause must be based on facts and circumstances, not feelings and beliefs. A person cannot be legally arrested for “looking guilty” or “acting suspicious”.

This same standard applies to search warrants, the seizure of property and the seizure of evidence. In order to get an arrest warrant or a warrant to conduct a search of a property, the police must present enough facts that would convince a reasonable person that:

- A person committed an offense

- A person who committed an offense resides at a particular location

- A property contains evidence related to a crime or was the scene of a crime

- Certain property was used in a crime or taken from the scene of a crime

This issue of probable cause is very important in the American justice system. It requires police and the courts to use solid evidence to make arrests and prosecute people, rather than beliefs and circumstantial evidence.

Probable Cause vs. Reasonable Suspicion

There is another important aspect of law enforcement call reasonable suspicion. This is a similar concept to probable cause but there are some important distinctions between the two. While probable cause is based on language in the Constitution, the concept of reasonable suspicion is based on a 1968 ruling from the Supreme Court.

The decision states that a police officer has the authority to briefly stop, question and conduct a limited search of a person if, based on their training and experience, they believe that a person is involved in criminal activity.

The amount of facts that are used to reach the standard of reasonable suspicion is lower than the amount used to establish probable cause. For example, if a police officer investigating a report of vandalism finds broken glass and graffiti at the scene of the crime and then sees a group of people several blocks away with spray paint on their clothes, the officer may have a reasonable suspicion that the group may have been involved in the vandalism.

Based on their location and the paint on their clothes, the officer may stop the group and ask them what they are doing and why they have paint on their clothes. He may conduct a limited search to check for evidence in their clothes or on their bodies. If he finds additional evidence, he may place the group under arrest. However, he cannot arrest the group simply because he suspects that they committed the vandalism.

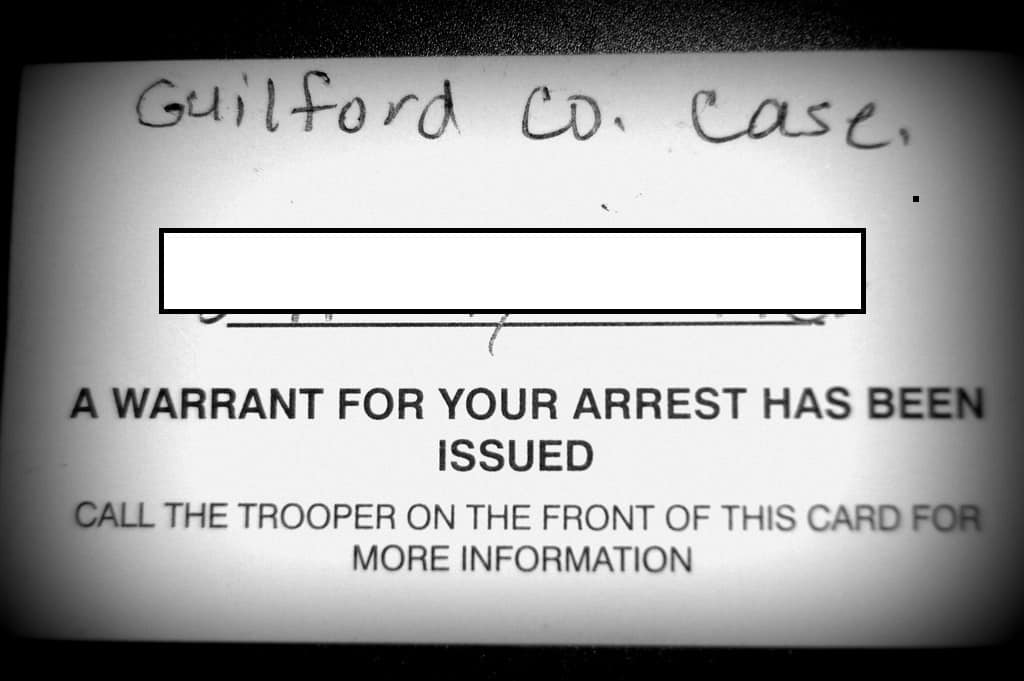

Probable Cause and Warrants

In most cases, a police officer must obtain a warrant from a judge in order to seek a person out for arrest or to search a property. However, there are some situations when there is no need for a warrant.

For example, if an officer is pursuing a suspect and the suspect runs into a house, the police do not have to stop and get a warrant before entering the building. Also, an officer does not need a warrant to seize evidence that is in plain sight of a location where the office is legally allowed to be.

If a police officer violates the standard of probable cause, it may be possible to have charges dropped. Consulting with a defense attorney is the best way to explore this legal defense option.

If you’ve been arrested without cause, we’re on your side. Contact attorney Brett Podolsky to protect your rights and fight for your freedom. Call 713.227.0087 today.