Ponzi Schemes and Texas Fraud Laws

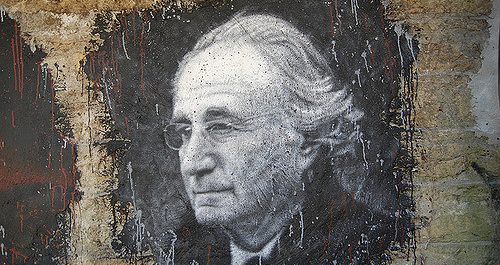

Over the past decade, a number of financial frauds have been uncovered by both federal and Texas investigators. The monetary value of these fraudulent operations has been staggering, ranging from in excess of $70 billion in the case of Bernie Madoff’s long-running Ponzi Scheme to a few thousand dollars typical of social media-based Pyramid Schemes such as the “Blessing Loom” scam currently operating on Facebook.

Regardless of whether or not those promoting such dubiously legal financial schemes actually believe that they are doing nothing wrong, there are federal and state laws that provide for substantial prison sentences and fines for those convicted of directly profiting from such illegal operations.

Texas Criminal Laws and Ponzi Schemes

Under Texas law, Ponzi and Pyramid Schemes are prosecuted using the same statute (Texas Business and Commerce Code, Title 2, Chapter 17, “Deceptive Trade Practices”) even though the two differ in how each scheme “feeds” itself and its founders.

In a Pyramid Scheme, the original investor is expected to recruit other investors in order for the original investor to “move up” in the organization. The original investor is paid for each new investor that he or she recruits and receives a percentage of the money brought in by each new investor.

In a Ponzi Scheme, the initial investors’ dividends are paid from money drawn in from newer investors who, in turn, are paid from funds that are taken from even newer investors. Unlike the pyramid scheme mentioned above, a Ponzi Scheme will eventually “implode” or “collapse under its own weight” if enough new investors cannot be recruited to pay the older investors.

Technically, Pyramid and Ponzi Schemes are not the same because a Pyramid Scheme actually “sells” something: an opportunity to recruit others. In a Ponzi Scheme, the investors are passive actors: they do not participate in selling or promoting the scheme to others except for the occasional “word of mouth” recommendation to friends or business associates.

Regardless of what the alleged crime is called, the penalties that can be imposed upon conviction are among the most severe allowed under the Texas Penal Code. It is not unusual to find that the prosecutor in one of the more “high profile” financial schemes intends to seek the maximum punishment available for the alleged creator of these schemes: a first-degree felony (from 5 to 99 years in prison and a fine of $10,000 per count of the indictment)

Defenses Against Ponzi Scheme and Financial Fraud Charges

Defense against a charge of financial fraud can be difficult, though now impossible, because there will almost invariably be a criminal charge and a civil lawsuit against the defendant. As an example, there could be a criminal prosecution alleging fraud followed by a civil lawsuit seeking damages using the same evidence that was presented in the criminal trial. Another problem that can arise is that of a RICO civil lawsuit.

There are two distinct legal actions that can arise from the federal Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organization (RICO) Act: a criminal prosecution and a civil lawsuit, also known as a “Civil RICO.” In a RICO criminal prosecution, the full force of a federal investigation is brought to bear on the defendant(s) in an attempt to demonstrate that federal laws were systematically broken, on a continuing basis, for the benefit of a select few or even a single “kingpin.” Upon conviction, each count of a RICO criminal indictment can be punished by 20 years in federal prison, a fine of up to $250,000 or twice the proceeds of the RICO operation, and forfeiture of any assets that were obtained through criminal activity.

In a civil RICO case, a private citizen may bring a lawsuit alleging that the citizen has been harmed in some way by an enterprise that was operated in an unlawful manner. If the case is proven, the defendant(s) can be ordered to pay three times the amount of damages that were originally sought.

In addition to the federal RICO Law, every state has its own RICO statute. In Texas, the RICO Statute is found in the Texas Penal Code, Title 11, Chapter 71, Section 71.02.

Regardless of whether the charges are related to alleged federal or state RICO crimes, or if the civil lawsuit is filed in federal or state court, the defenses that can be raised are similar. In criminal proceedings, the prosecution must prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the defendant was aware that his or her conduct was illegal but persisted in that activity for personal gain.

Defenses that may be raised to criminal RICO charges include:

- The defendant was not involved in, nor profited from, a criminal activity.

- The defendant was not aware that the activity was criminal.

- The defendant participated in the activity, but was unaware of the criminal activity of others.

- The defendant was also harmed by the criminal activity.

In a civil lawsuit, the burden of proof is still on the plaintiffs, but now that burden needs only to be met by a “preponderance” of evidence. Thus, it is often the case that a criminal prosecution may fail while a civil lawsuit results in the awarding of considerable damages to the plaintiffs.

As can be seen from the above discussion, a successful defense of financial fraud charges will be both a time and resource-intensive undertaking that may not reach trial for several years. It is suggested that anyone accused of such crimes, or who finds themselves the target of a civil lawsuit seeking damages from an alleged financial fraud enterprise, contact a criminal defense attorney as soon as they become aware that a case against them is pending.